So You Want to Hear a Story, Eh? GamerGate and Media Narratives

Sorry, this will be another discussion of GamerGate (let it be the last one); the latest skirmish that doesn’t matter from the culture wars that I can’t stop clicking on. Every crappy blog needs a post whining about an article from a far more noteworthy publication with which they disagree. I guess I’m getting mine out of the way now.

For almost two years I’ve been listening to the New York Public Radio show On the Media distributed through NPR. I’m slowly making my way through their immense archive that goes back to 2001. They’ve been “explaining the news” long before it was cool.

NPR recently adopted the admirable editorial policy of avoiding false balance. NYU journalism Professor Jay Rosen notes the two most important bits:

In all our stories, especially matters of controversy, we strive to consider the strongest arguments we can find on all sides, seeking to deliver both nuance and clarity. Our goal is not to please those whom we report on or to produce stories that create the appearance of balance, but to seek the truth

…

At all times, we report for our readers and listeners, not our sources. So our primary consideration when presenting the news is that we are fair to the truth. If our sources try to mislead us or put a false spin on the information they give us, we tell our audience. If the balance of evidence in a matter of controversy weighs heavily on one side, we acknowledge it in our reports. We strive to give our audience confidence that all sides have been considered and represented fairly.

SMBC Theater explains what happens when the news media attempts to be objective by treating both sides of an issue has offering equally strong arguments, as if they both cancel each other out:

The NPR model works well for issues in which researchers conducting multiple, large, well-controlled, peer-reviewed studies have reached similar conclusions. It also works for less-scientific issues in which mountains of evidence clearly lie on one side of the argument. Just because a former Navy SEAL writes in his memoir that his buddy totally saw WMD in Iraq doesn’t mean journalists should give weight to his unsupported claim by covering it.

However, the model is not very useful for covering a broad-based social movements, particularly social media activism. Let’s look at the nature of this kind of Internet activism to understand why the “balance of evidence model” can lead to crappy coverage.

1. Joining an online campaign is easy.

To participate in the conversation one only must like, share, reblog, retweet, or comment. The discussions within the early 20th century labor movement in the U.S., the Civil Rights Movement, and the early environmental movement, among others, were often held in print publications. So, if you wanted to participate in the conversation, you had to get your comments past newspaper and magazine editors.

2. Nothing is official.

There are no leaders in online social media activism. A single person might start a Twitter hashtag. A particular online community might have strict moderators or prolific users that guide discussion. But no one can claim to speak for the movement in any sort of representative way. There’s no official body to publish goals, or condemn certain tactics. Meaningful self-policing is nigh impossible.

3. Again—anyone can join.

Including trolls who couldn’t care less about either side, seeking simply to provoke people and create drama. Including sockpuppetry both from those who agree or disagree with the movement, who seek to carry out vote brigading, post anonymous attacks, or surreptitiously post inflammatory content in the name of their opponents.

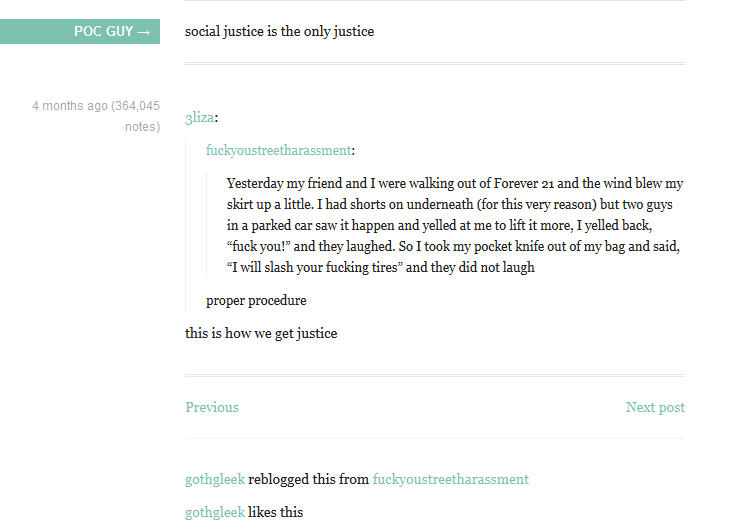

To illustrate this point, a friend (who I’ll call Alice) and I argued whether the “notes” (likes and reblogs) on a Tumblr post can be used to extrapolate the number of Tumblr users who agree with the sentiment of the post. Below is a screenshot of the post in question. If I remember correctly she found this on r/TumblrInAction or some such place.

Alice’s argument was thus: opinions in a population follow a bell curve. Depending on radicalization, the bell curve may be shifted, or have larger or smaller standard deviation. In any case, approximately 5 percent of a population lies beyond two standard deviations from the mean. It’s reasonable to assume these are the “radicals” of a population. If we assume that one “note” equals one person, and there are over 360,000 notes, then 2.5 percent of those notes is 9,000 people. So 9,000 people on Tumblr think brandishing a weapon and threatening property destruction is a reasonable response to catcalling.

I haven’t an earthly idea if those statistical assumptions are correct or applicable in this case, but the bigger problem that I see is that Alice is assuming those 360,000 people constitute a representative sample of Tumblr users. I think it’s quite likely that many if not most of those notes are the result of someone who trawls Tumblr for outlandish opinions and posts them to r/TumblrInAction.

We might find more precise numbers via a content analysis. However, we’d have to distinguish between honest opinions and “ironic” notes, for lack of a better word. We’d have to take sock puppet users into account. We’d have to account for vote brigading. However, all of this excludes the very real possibility that this anonymous submission to fuckyoustreetharassment.tumblr.com is in fact a stealth parody, written with the intention of satirzing Tumblr users, feminists or both. And if it is, how many people who liked or reblogged the post recognize that it is one?

This isn’t to say that the news media shouldn’t cover social media activism or that it’s impossible to derive anything meaningful by studying it. For example, Andy Baio recently conducted an analysis of GamerGate tweets over a 72 hour period. However, like any such analysis, it’s unable to tell journalists what they must know before any meaningful editorializing; how many people support what?

So keeping the three points outlined earlier in mind, note that journalists like simple narratives. They want afflicted to comfort and comfortable to afflict. GamerGate makes for an easy story for them to write and for readers to understand.

Some journalists like Casey Johnson at Ars Technica might conclude that a handful of screenshots of anonymous chat logs and discussion board posts from a single online community is sufficient to deduce the motivations, attitudes, and identity of the tens of thousands of people who tweet and retweet a particular hashtag. (Ars editor Kyle Orland thought it was unfair and misleading when similar evidence was used to draw conclusions about the motivations, attitudes, and actions of him and his colleges in the gaming press.) However good journalists recognize that reality often fails to follow a tidy narrative. So what can good journalists following the “balance of evidence” model accurately say about Internet activism?

“This hashtag has spawned a lot of discussion online with an x number of shares.”

“This person says she’s received anonymous threats which he attributes to Group A. Police say they are investigating.”

“Some comments ostensibly in support of the movement are inflammatory. Many members of a popular online community for Group A have written comments condemning threats and personal attacks.”

Of course this stuff sounds a lot more banal and uninformative without all the editorializing.

Unfortunately this is how On the Media opened its recent coverage of GamerGate. in host Bob Garfield’s interview with Polygon editor Christopher Grant:

GARFIELD: Though women now represent half the video gaming community, a Pew study this week revealed that gaming is the least welcoming online space for women. The conclusion seems to be borne out by the ongoing troll crusade known as #Gamergate, wherein a small rabble is using a trumped-up scandal as cover for a full-on attack on female game-makers and game critics. Until the story materialized in the New York Times last week, one influential gaming publication, called Polygon, did its best not to feed those trolls, but finally weighed in with a letter from the editor, Christopher Grant. Chris, welcome to OTM.

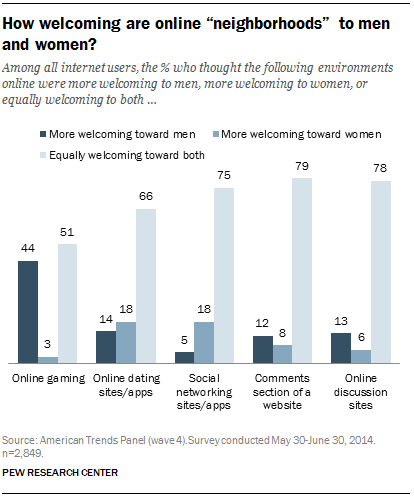

Here’s the Pew study Garfield cites. Below is a chart from the report.

To say “gaming is the least welcoming online space for women” I suppose is a correct interpretation of the study, but Garfield would get full points if he reported Pew’s full explanation:

Fully 44% of internet users believe online gaming is more welcoming to men, while just 3% believe it is more welcoming toward women. Half believe it is equally welcoming to men and women, a proportion much lower than any of the other environments.

While most online women believed online gaming was equally welcoming to both genders (55%), a substantial minority believed it was more welcoming to men (40%). Men were more likely than women to think online gaming was more welcoming to men, 49% vs. 40% [emphasis mine].

These aren’t numbers male gamers should be proud of, to be sure. My fellow male gamers should be embarrassed and ashamed that so many women think they are unwelcome or less welcome to participate in our pastime. But, as I said before and will likely be saying a lot more in the future, the numbers don’t jibe with the narrative. I’ve heard the gaming community was a hotbed of misogyny. Where women are resoundingly unwelcome and constantly harassed, resulting in many would-be women game developers leaving the industry in droves.

At the very least I was expecting a majority of female respondents to report that they felt online gaming was an unwelcoming environment.

But if the supposed oppressors in this narrative think a community is more unwelcoming than the supposed oppressed do, then perhaps the narrative is balderdash.

Moving on, Garfield informs listeners that GamerGate is “the ongoing troll crusade…wherein a small rabble is using a trumped-up scandal as cover for a full-on attack on female game-makers and game critics.”

Wonderful! Such unequivocal language means we’re finally going to hear how GamerGate’s leaders orchestrated the anonymous threats against Quinn, Sarkeesian, Wu, and others. (And I guess we’re also about to learn exactly who GamerGate’s leaders are!) We’re going to hear about extensive opinion polling and/or social media analytics whereby we learn that most GamerGate supporters also support rape threats and death threats.

Of course, what we actually hear more of that armchair psychoanalysis about how GamerGaters are Tea Party-esque reactionaries, terrified at the prospect of sharing their pastime with new faces.

GRANT: In reality it’s a, it’s a re-balancing. Video gaming on the heels of its 2011 Supreme Court victory, increasing sales, increasing software and tools that make making games open to more people than ever. As it grows into that, I think a lot of people have a lot of concerns about new voices. Voices that are often times critical of what’s come before, entering the fray. It’s an old war. Right? It’s the battle against progressive voices. What they see as political correctness being inserted into a formally “safe” space. It is a culture war.

It’s an interesting opinion. Too bad it’s offered sans facts or any evidence at all. I’ve said previously that I find the ‘gamers are frightened of new voices’ line unconvincing both because of my personal observations of trends in gaming criticism that gained steam long before people started lining up to claim victim status from GamerGate, as well as recent polling data on Millennial attitudes on diversity. Of course, it’s entirely possible gamers are generally progressive but hold reactionary attitudes about gaming. I’ve yet to see any data that backs up the “Tea Party” theory of GamerGate.

GARFIELD: The kinds of complaints that we heard about gaming and its occasional misogyny, its sexist characterization of female characters and so forth. We’ve heard them about the larger popular culture for decades. But there is not a concerned effort to attack and threaten the critics. Why do you suppose that this subculture of gamers has been so, uh, well…vicious?

GRANT: It’s accepted to criticize these tropes. And fail the Bechtel test, the Bechtel test being two women having a conversation that isn’t about a man. Every year, plenty of movies fail that test. Gaming was under-analyzed, right? It was shunned from academia. Under-critiqued. But a lot of the criticism that’s also been leveled against games has been hyperbolic. A bad faith effort. There’s not shortage of examples of the main stream media vilifying games. And getting basic facts wrong. So, a lot of the gaming audience looked at that criticism and learned a certain way of responding to it. Which is that it’s wrong. It’s ignorant. And then when criticism from inside happens. Criticism about the way women are presented. One example that’s very notable here - they deal with it in a sort of hysterical way. In a reactionary way.

And here I was thinking that the GamerGate blaze is torching its way though a pile of dry tinder in the form of an ever-increasing stream of hyperbolic, inaccurate prejudice-plus-power-infused blather produced by the gaming press.

GARFIELD: Do we even know who the ‘they’ is?

GRANT: We know who some of those people are, right? A lot of them are anonymous. Gamergate would be quick to say – well that’s not who we are. It’s this logical fallacy where they can define a movement whose inclusion is exactly ten characters long. All you need to do to be a member of this movement is type #Gamergate in Twitter. And so they’ll reject any behavior that they don’t want. While basically condoning it and allowing it and boosting it. It’s this very strange intentionally chaotic mission. Where they reject basic order and structure. So as a journalist it’s really hard to tackle it. And the only benefit I can see of being leaderless, of being amorphous is that they can continue their campaign of harassment with little to no culpability.

Wait, if GamerGate supporters aren’t allowed to define their movement, then why does the media get that privilege? How exactly does the ability of any jackass to sign up for a Twitter account mean GamerGaters are “basically condoning it and allowing it and boosting” threats and harassment? Why is it so easy to find examples of GamerGate supporters condemning (and reporting) threats and harassment? With no leaders to decide anything, how did this leaderless social movement decide it would remain leaderless and unorganized?

I presume Grant has been on the Internet long enough to know that Twitter hashtag campaigns don’t have leaders or a vetting process. People see something going on and decide to join in. A few months ago, many women took the opportunity with #YesAllWomen to describe the “obstacle course of sexual menace,” to quote Jordan Klepper, though which they navigate daily. No one made the idiotic suggestion that the movement was intentionally remaining “leaderless” and “amorphous” so asinine nonsense could be freely posted in news publications and the Twitterverse.

Finally on this point, the notion that the gaming press has struggled to “tackle” GamerGate is beyond farcical. It found a ready-made, incendiary culture war narrative and has flogged it relentlessly.

BOB: IS there any public face. Is there anyone who is willing to attach his – I assume his – to this whole supposed scandal.

GRANT: Their actually is a notable her, Christina Hoff Sommers. She’s a scholar in residence at the American Enterprise Institute which is a right-leaning think tank. She has no interest in video games. But she was interested in maybe getting some new converts to her particular ideology. A lot of cases the people who are signal boosting this topic, don’t have anything to do with games. People like Adam Baldwin who uses his platform on Twitter to sort of amplify a lot of this stuff. He’s not a gamer. He doesn’t have an interest in this culture. It’s a political platform. A lot of the Gamergate adherents are really happy to embrace these opportunists. They call Christina Hoff Sommers ‘mom’ – it’s a very strange, I don’t know, almost like hunger for validation. They do not have a lot of public faces. The ones that they do have they are very attached to.

From what I could tell, it seems most male gamers, up until GamerGate, considered themselves fairly progressive. The culture wars to them meant comical right-wing hysteria like Bill O’Reilly’s rants about the War on Christmas. But when progressive culture warriors came for gaming, conservative culture warriors swooped in to explain to bewildered gamers why they were under attack, offering a counter-narrative about “liberal media bias” and the “radical feminist agenda.”

While he makes much of the various right-wingers who’ve attached themselves to GamerGate, Grant ignores GamerGate’s wider diversity. In Dan Auerbach’s Oct. 28 Slate stratagem for tricking the Grangerfords and the Sheperdsons of GamerGate into stopping, he lists the failed tactics of GamerGate critics, among which is the “[c]convenient erasure of Gamergate’s many female, LGBTQ, and minority members, however wrong they may be.” Here are some of those folks who’ve added their names and faces in support of GamerGate, including game developers and journalists who Grant has ignored. My favorite example is game dev David Jaffe who was for GamerGate, before announcing that he feels he has to condemn it (but still supports it).

To end, I’d like to ask you to compare Bob Garfield’s interview with Chris Grant with this On the Media piece on featuring ad debate between two journalists about news coverage of Israel-Palestine. Moderating a debate between two seemingly intractable sides of a controversial issue is harder than agreeing with someone over how much you agree with them, but the listener comes away with a far deeper understanding of the issues. (I found Friedman’s conspiratorial view that reporters covering the Gaza war went out of their way to avoid shooting footage and photos of Hamas fighters unconvincing, but his point about erroneously simplistic narratives is well-taken.)