UPDATED March 2016: More on Why Anonymous Comments are Useless

I talked a bit about GamerGate last week and how befuddled I was over how the gaming press continues to point at and fan themselves over the outrages shat out to us by anonymous people on the Internet. I’d like to explain exactly why this is point sticks with me.

Last year, NPR media correspondent David Folkenflik spoke with On the Media’s Brooke Gladstone about his new book Murdoch’s World: The Last of the Old Media Empires. He explains some of the sockpuppetry once practiced by the Fox News PR department:

There’s a long stretch, years where people working for Fox News PR were not only supposed to spin and send out press releases and get good publicity for their people, but late at night they were supposed to be on the blogs, responding to every negative and even neutral blog posting, no matter how large or small the following that that post might have. So one person said she had over 20 aliases that she used to file these comments. Another person had over 100 aliases. They had to use laptops that had been bought from secondhand stores and repurposed and not purchased on corporate credit cards because their bosses didn’t want it traced back to Fox News or the News Corp. They didn’t just respond to the postings. They responded to other people’s comments. So one PR person described getting a call, being woken up at 2:30 in the morning, by the woman who’s now the head of PR for Fox, Irena Briganti, and she said, why are you embarrassing me like this? And the person said, what do, what do you mean, having been just woken up. And she says, you know, you haven’t responded to comment #67, or whatever it was on this posting.

I’m always surprised at the lengths to which groups with a persecution complex will go to become the very people they fear and hate. But yeah, anonymous comments. You don’t know who wrote them. You don’t know what their motives are. Attempting to extract genuine sentiment, ideological leaning, or demographic data from the content of anonymous comments either makes you a fool or a hack with an agenda.

UPDATE:

I’m surprised I didn’t see this earlier. Shortly after dozens of stolen photos of naked celebrities were leaked online a month ago, Emma Watson delivered a speech at the UN, urging men to to fight discrimination against women. A group apparently linked to 4chan then threatened to release nude photos of Watson in retaliation. News outlets breathlessly reported on this new violation about to be inflicted on another woman by the misogynistic Internet. Except it was a hoax by people who were apparently attempting to have 4chan shut down. Of course the same journalists who fell for that prank are now breathlessly reporting on every new anonymous threat participants in the GamerGate story say has been leveled at them.

UPDATE #2:

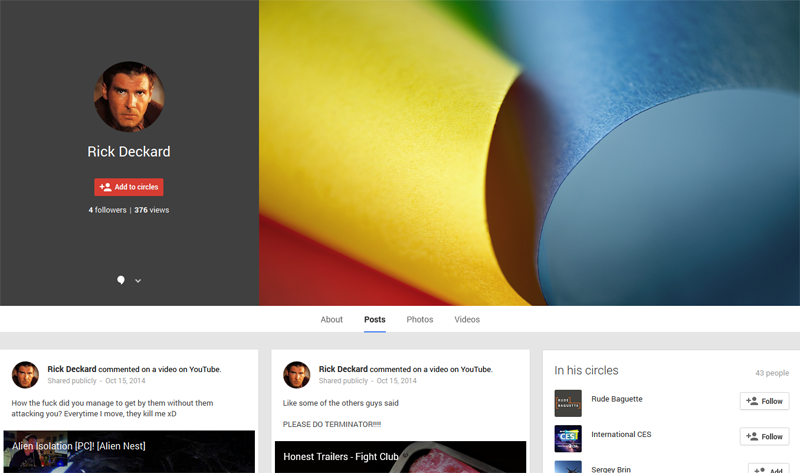

Another quick addendum. My college professor who inspired/assigned me to create my own website is a strong advocate for using one’s real name and standing behind one’s words. And while agree that, in most cases, we’d all be better off if we avoided anonymity on the Internet, it’s not as if online services that attempt to coerce people into giving out their real names are sources for honest opinions. Case in point, these Google+ users.

UPDATE #3:

Video game reviewer Alanah Pearce got tired of the torrent of rape threats and death threats, but instead of writing articles blaming gaming culture or male gamers, she identified the Little Sh*ts and told their mothers. Also, and it’s not like we didn’t already know this, but just as anyone can join #YesAllWomen or #GamerGate, anyone can send rape threats.

UPDATE #4

A 2016 Bloomberg piece profiles a hacker named Andres Sepulveda who, for nearly a decade, was hired by political campaigns throughout Latin America to break into oppoents’ computer networks, steal campaign strategies, install malware, and manipulate social media on a massive scale:

He also splurged on the very best fake Twitter profiles; they’d been maintained for at least a year, giving them a patina of believability.

Sepúlveda managed thousands of such fake profiles and used the accounts to shape discussion around topics such as Peña Nieto’s plan to end drug violence, priming the social media pump with views that real users would mimic. For less nuanced work, he had a larger army of 30,000 Twitter bots, automatic posters that could create trends. One conversation he started stoked fear that the more López Obrador rose in the polls, the lower the peso would sink. Sepúlveda knew the currency issue was a major vulnerability; he’d read it in the candidate’s own internal staff memos.