A Failure to Communicate: Why Everything Probably Isn't a Conspiracy

For a year in middle school, I carpooled with the family of a girl whom I’ll call Suzanna. Her mom or dad would take me to school in the morning on their way to work and my dad would drop her off at home in the afternoon.

Suzanna and her family were all very kind and generous people. If we had enough time in the morning her mom would stop at the Bashas’ near my house and buy us soda and snacks.1 My dad wanted some way to repay Suzanna and her family for ferrying his smart-assed spawn to school every morning, so one day, upon picking up Suzanna, he asked her if she’d like to get something to eat with us when we picked her up the next day. Suzanna said sure, that would be great.

I’m almost positive either Dad or I told her to make sure her parents were okay with that first. We didn’t want to spoil her dinner or anything.

So the next day, we all go out to eat after school. We had a great time, it was a lot of fun. Upon returning home, we found that Suzanna had not in fact informed her parents of this outing.

Her mother was so worried that her daughter had not returned home on time that she called Arizona’s highway patrol. Neither Dad nor I owned cell-phones at the time, nor if I remember correctly, did Suzanna, so there was no way of contacting any of us while we were out. Dad was very confused. What was Suzanna’s mom so worried about? We were only out for about an hour more than usual. I was what they’re calling nowadays a free-ranged kid so I imagine Dad wouldn’t be too worried if I were gone for that long.

Dad’s adorable naiveté about this whole situation was made more ironic, considering that he, like millions of other Americans, watched (and still watches religiously) Dateline NBC and those other TV news magazines that indulge in “true crime” reporting.

It took me a few tries, but when I was finally able to get Dad to understand what was likely racing through Suzanna’s mother’s mind throughout all this, he was horrified and upset that I would consider such a thing. It certainly never entered his head.

At this point, I’ll mention that Dad’s an immigrant. He came to the U.S. from Thailand in the early ’80s. Even my 14-year-old self wondered if that colored how this whole thing was perceived.

Children of first-wave immigrants, or anyone who’s seen “Shit Asian Dads Say,” understand how a less-than perfect command of English and a, let’s say developing, understanding of American social conventions can often result in (usually) hilarious situations.

In any case, the confusion was cleared up and Susanna and I enjoyed the carpooling services of each other’s families for the rest of the year, including detours for junk food and slightly-better-than-junk-food food, though this time with more perspicuous parental notification.

I tell you this story, dear reader, in an attempt to illustrate how easily ominous conclusions can be drawn from the mundane.

Because if Meredith Haggerty and the producers of “Quiet, Wadhwa,” the Feb. 6 episode of On the Media’s 2 spin-off podcast on Internet culture, acknowledged this, they could have produced something much more interesting than the deeply flawed episode they actually made.

At the time of this writing the original piece has been removed and replaced with the following note:

TLDR episode 45, published Friday, February 6, has been removed. We are working on a piece for On the Media that will include a range of views on advocacy for women in technology.

Addendum: WNYC decided to remove this episode, because it centered on an internet debate about author Vivek Wadhwa and we failed a basic test of fairness: we did not invite him to comment. We are planning a follow-up that will address both the original issue and the ensuing conversation around the removal of the episode. We are keenly aware of the discussion out there and will release the new piece as soon as it is ready.

I’ve reposted the 11 minute segment here. Give it as listen as I’ll be discussing it in detail.

So if TLDR is now scrambling to produce a segment that “includes[s] a range of views on advocacy for women in technology,” then what did they actually produce on the Friday last?

The episode is a discussion of Amelia Greenhall’s recent blog post about an academic/tech entrepreneur named Vivek Wadhwa, who has positioned himself as an advocate for women in tech. A position that some (many? most?) women in tech would prefer be filled by actual women in tech.

Greenhall, an accomplished woman in tech, describes how Wadhwa became the go-to authority on the subject by “trading up the chain”; leveraging the publication of one’s work in one outlet in order to get it published at bigger and better places.

Readers, correct me if I’m wrong, but I’m pretty sure trading up the chain is how the publishing industry works. It certainly doesn’t make Wadhwa an expert on women in tech, but it doesn’t show why he shouldn’t be writing about it either.

Greenhall’s issue with Wadhwa is that he’s “taking up space,” and “sucking all the air out of the room” by getting published and quoted by journalists on the issue of women in tech instead of actual women in tech. But is that Vivek Wadhwa’s fault or the fault of the editors and journalists who’ve published his work and sought his comments?

Wadhwa should turn down interview requests on stories about women in tech and point journalists towards “someone more qualified,” says Greenhall at the end of the piece. And while I agree it would be nice if, for example, the co-architects of the current horror show in the Middle East stopped opining about America’s foreign policy and handed the mic to someone else, you know an idea is bankrupt when the proposed solution is for discredited pundits to self-deport from the conversation.

Why do journalists get a pass here?

I’d like to hear why the editors of the various outlets in which Wadhwa’s writing have been published chose to hear from him. I think it would be quite revealing to hear the criteria by which journalists deem someone an expert whose voice deserves to be heard over others.

But instead of exploring those issues, the discussion turns to Wadhwa’s perceived creepiness.

Much is made about Wadhwa’s “token floozies” comment. I would tell you more, but I don’t really know much more. In the TLDR episode Greenhall just repeats what she wrote in her blog post:

There was the “Floozies” incident. Basically Vivek got on stage at a Bloomberg conference in January 2014 and talked about the importance of hiring women in influential leadership roles, not just as “token floozies.” He tried to ignore the criticism for several days, including a blog post by management consultant Mary Trigiani calling him out for it. He then published a condescending public response to Trigiani that belittled and gaslighted her as having “personal difficulties.”

The full context of Wadhwa’s words seem important here. Is he saying that all or most women in tech are “token floozies”? Is he saying that “token floozies” is what the boards of tech companies want, and that this is a bad thing?

Few things are more suspicious than a narrative crafted around a two-word quote from a lengthy speech. If the context supports the claim, people are pretty eager to show the full context.

However, the Daily Beast article Greenhall links to doesn’t link to the actual talk Wadhwa gave. Nor does Trigiani’s blog post. I’ve done some searching for the talk, and while I can find a number of Wadhwa’s talks, I can’t find one from the “Hacking Gender” Bloomberg conference in January 2014. If anyone knows where I can watch/listen to it, please let me know.

Wadhwa’s “condescending public response” was posted by him the the comments of Trigiani’s post and on Medium. His response is dismissed out of hand with another two-word quote. Here’s the paragraph where Wadhwa supposedly “belittled and gaslighted [Trigiani] as having ‘personal difficulties’”:

When, later in the evening, someone pointed out that the slang word that I used had a different meaning than I thought, I apologized profusely. I felt really, really horrible and I literally lost sleep over this. You, on the other hand, stormed away and behaved in a highly unprofessional manner. I asked several people why you were reacting this way and they said that I should ignore you because you had “personal difficulties”. A couple of people said you had a reputation for behaving in this manner. I did not want to ask more because I was not sure of what was motivating you to behave the way in which you did. That is why I chose not to respond to your barrage of angry tweets.

And here are the paragraphs from Trigliani’s blog to which it appears Wadhwa was responding:

By Tuesday evening, I was enduring the remarks of a so-called expert in talent who fretted that “token floozies” in companies like are not truly women of the tech workforce. Who then refused to explain what he meant. For two days now.

You see, he expects only to pontificate. To not answer questions unless they are posed in a way that flatters his ego and sustains his superiority, both in the asking and the answering. Should this man be challenged, watch out. He cites Duke University, Stanford University, Singularity University, WASHINGTON POST, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL and startup Trove as the stars in his CV, and so far, they see no need to call for an explanation, either. Rumor has it he has a book coming out about how women are leaving tech employers in droves.

So in context, we see that Wadhwa was in fact responding to her challenge for an explanation.

In context we see that Wadhwa’s “gaslighting”3 could also be just as neatly interpreted as Look dude, I heard you were going through some heavy shit, so figured it would be best to not respond, but now you’ve slammed my work on a public forum, questioned the intentions behind my work, and accused me of being unwilling to respond criticism, so now I’m responding.

On the claim that Wadhwa is frequently “condescending” or “paternalistic,” I’d like to remind everyone that he is a professor at two “Ivy-plus” schools. He’s written books and his articles have been published in national newspapers.

I’m not saying any of that qualifies him to opine on so much as the opening of a new jogging path in San Jose, but college professors are pretty damn condescending and paternalistic, not just towards women in tech, towards everyone.

Heck, my uncle is a retired elementary teacher and if someone pushes past him on the subway, he has to fight the urge to stop the young man and lecture him on manners.

So if one criticizes Wadhwa’s work—as everyone should be able to—it shouldn’t seem crazy that he might go into professor mode, assuming that the disagreement is due to his failure to effectively express himself, and that if he keeps trying, eventually everyone will agree with him.

Even if that isn’t an accurate assessment of his behavior—which it very well many not be—it’s no less unreasonable than Greenhall and Haggerty’s apparent assumption that Wadhwa acts like a paternalistic, condescending prick when he converses with women.

But perhaps Wadhwa was wrong to mention “personal difficulties,” whether or not they indeed exist, in a public venue, yes? They are “personal” after all. Maybe it would be better if he tried communicating to his critics via a more informal platform? Maybe he could be more easily understood in a more casual conversation?

Well if you listened to “Quiet, Wadhwa,” you know where I’m going next.

“He has a tendency,” darkly intones Haggerty, “to DM” or direct message his female critics on Twitter.

Greenhall describes Twitter’s DMs thusly:

It’s really like this non-consensual, “let’s go over here, where people can’t see you criticizing me, maybe I can talk to you there.” Wadhwa has done this to several women.

Haggerty: It really feels like the Twitter DM can be like the “hand on the knee” of social communication.

Greenhall: I don’t follow that many men because I’ll see them through Twitter lists, but if you’re mutually following them, that opens up that DM channel and you just get a lot of unwanted private messages that are pretty gross usually.

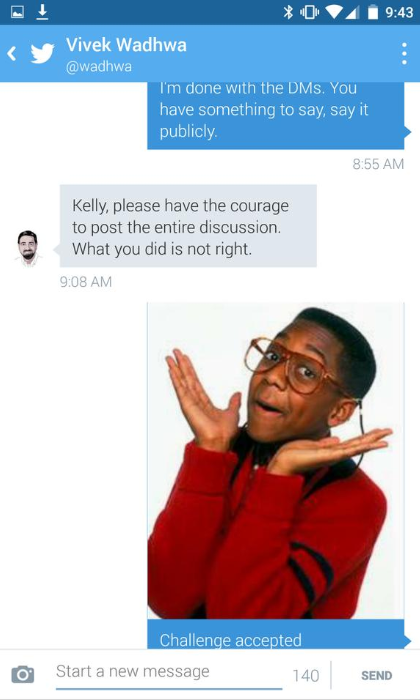

That’s a hell of a lot of intent being ascribed to Wadhwa. First, Greenhall’s insinuation that Wadhwa is using Twitter’s direct messaging system to send untoward messages to women to ensure that their responses are not public is undermined by screenshots taken by Kelly Ellis, a woman he messaged, in which he asks her to make the entire discussion public:

Ellis posted two sets of screenshots of her DMs with Wadhwa here and here.

The other element of intent placed on Wadhwa is that everyone knows that only creeps who send “gross” private messages send Twitter DMs to women and yet he sends them anyway.

First, it’s not clear that Wadhwa is aware of that convention. Do many or most male Twitter users know how some/many/most women view DMs? Maybe the guy who promotes himself as an advocate for women in tech should know these things and by being unaware he further crystallizes why he should stop.

But even if Wadhwa is aware, to whatever extent, of how (most? all? some?) women perceive DMs, it’s quite possible that the idea that he could come across in such a manner, just as the notion that a mother might—for completely understandable reasons—grow increasingly worried when Suzanne should have been home 45 minutes ago and was last seen with that middle-aged foreign guy she doesn’t know too well, never crossed Dad’s mind either.

Regardless, the aspersions continue to fly. In his direct messages, Greenhall notes that Wadhwa repeatedly invites the women he’s conversing with to continue the discussion in person:

He asks them to come meet him, like, “meet me in person,” “come to Standford,” “come to my office,” “come meet me,” “come sit on my lap, you bad, little, young woman.”

Indeed, Wadhwa could be attempting to lure women to his office for nefarious purposes. Or looking at it another way, maybe Wadhwa is frustrated that members of a group for whom he sees himself as an advocate are upset with him and the written word by which he makes his living isn’t helping, and in exasperation he asks some of these women to meet him to discuss this in person, hoping that maybe then they might understand that he is on their side. But for reasons for which he’s at fault (which I’ll get to below) and other reasons which are entirely unfair, they’ve stopped buying what he’s selling.

Of course, the sinister explanation makes for better radio.

In his response to Trigliani’s blog post on his “floozies” comment, Wadhwa blames his poor understanding of American slang, as he learned English in India, where the dialect contains far more Britishisms than American slang.

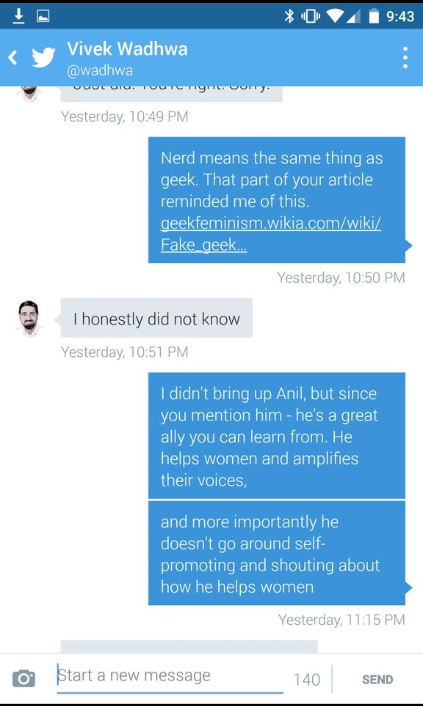

Wadhwa expresses similar confusion in a DM with Kelly Ellis:

Greenhall and Haggerty suggest that Wahdwa’s claimed misunderstanding even further disqualifies him from writing and speaking about women in tech. Greenhall argues that:

[e]ven if you do take him at his word, I think it’s totally disturbing. Has he really been this spokesman for women in tech for all these years, while he’s believing that women can’t be nerds, because that’s like super misogynist because VCs only want to invest in nerds and they have a lot of power in Silicon Valley and the Bay Area.

Wait, Wadhwa’s misunderstanding the nuances of certain American slang words is misogynist because venture capitalist firms only want to invest in nerds? Is Greenhall saying Wadhwa believes that? Has Wadhwa made that claim about VCs? Is there evidence to support that claim? Was there any actual reporting done in this episode?

I always thought “nerd” implied a sense of social isolation, whereas “geek” meant an obsessive knowledge about a particular thing; e.g. there can be sports geeks, music geeks, computer geeks, etc. There appears to be a wide variety of definitions of and connotations with the words nerd and geek in the American-English-speaking world alone.

Why must everyone subscribe to the same nuances of words like geek and nerd to comment on women in tech?

Haggerty and Greenhall then share Wadhwa quotes that confound them.

Haggerty: “Women should let the boys have their social media while they save the world.” What does that even mean?

Good question, Haggerty. Why didn’t you ask him?

I realize that this is an opinion piece. Amelia Greenhall has every right to publish her opinions. However, Haggerty and the producers at OTM and TLDR are journalists with an obligation to ensure that their broadcasts meet the ethical standards of their profession. Which compel journalists to:

– Take responsibility for the accuracy of their work. Verify information before releasing it. Use original sources whenever possible.

– Provide context. Take special care not to misrepresent or oversimplify in promoting, previewing or summarizing a story.

– Diligently seek subjects of news coverage to allow them to respond to criticism or allegations of wrongdoing.

“Quiet, Wadhwa” concludes with a list of genuinely scummy examples of his shameless self-promotion—including stealing bylines—over actions that would help ensure journalists heard more from women in tech, like actually pointing journalists towards women in tech.

But TLDR’s failure to meet “a basic test of fairness,” as the note on the removal page puts it, calls into question all of the claims put forth in the episode.

While I don’t think Vivek Wadhwa deserves to be the go-to guy on women in tech (more so than anyone else, at least), I don’t think it’s very productive to attempt to silence him in return for all his egocentric bloviating.

In the end, I think this incident will only serve Amelia Greenhall and Meredith Haggerty’s ideological opponents. The malicious intent they are certain they read in Wadhwa’s Twitter messages will be heard in the sloppy reporting, the episode’s removal, and whatever OTM comes up with to replace it.

But maybe they would have heard that anyway. There’s this quote I like from Sarah Miller writing for Time. It aptly diagnoses the problem with the simplistic narratives peddled by advocacy journalism. “While the world should certainly have respect for feminism,” Miller writes, “I’d like to see feminism have a little more respect for chaos and ambiguity.

To chaos and ambiguity. ![]()

UPDATE #2: (Feb. 22, 2015) Last Thursday, TLDR released an episode revisiting their "Quiet, Wadhwa" piece. You'll grimace through all 23 minutes of it, but it's quite illuminating.

TLDR producer Katya Rogers admits to being "in a bubble" when she and Meredith Haggerty produced the original piece. In an age of identity politics, I really hope journalists' ethical obligations to be fair and seek comment from all parties won't be tossed aside as an insidious method of silencing and minimizing those who journalists cast as the oppressor in their narratives.

It seems both Haggerty and Wadhwa thought that a long, mostly un-edited interview would vindicate their respective positions. The end result, however, is that both of them come off even worse.

Haggerty continues to appear oblivious to the implications of blithely characterizing someone's behavior as sexual harassment in a news broadcast.

Wahdwa refutes the accusations of financial impropriety, byline-stealing, and "taking up space" in the conversation which Amelia Greenhall leveled at him, but comes across as every bit the paternalistic, condescending prick that the original TLDR episode cast him as. Lots of lines like "these women don't understand how journalism works" and asserting how awesome an advocate he is for women and minorities.

Although I still think the problems with his tone are largely compounded by the cultural barrier through which he's attempting to communicate.

Since TLDR doesn't confirm Greenhall's accusations or deny Wadhwa's denials for the more easily confirmed claims regarding money and properly crediting people, I'm going to assume the accusations are bunk. Which means all we're left with is tone policing.

I'm sorry, but I can't agree that someone should be "quiet," as TLDR #45 instructs, because I or others dislike his tone.

-

A practice which I guess sounds rather negligent nowadays, but which Suzanna and I thoroughly enjoyed. ↩

-

I don’t mean to pick on On the Media again, but I listen to them a lot so I hear a lot more of their brilliant moments and their missteps than those of other news outlets. ↩

-

Gaslighting is a disturbing form of mental abuse. However, online the term is frequently wielded against anyone who suggests that the wielder’s interpretation of something may be incorrect. By suggesting that you didn’t mean for the wielder to interpret what you wrote in that way, according to this line of thinking, you are also suggesting that the wielder is crazy, and thus you are gaslighting. Scott Alexander explains this sort of motte-and-bailey stratagem here. People want to apply a term loaded with serious implications upon conditions that are far removed from the scope of the original meaning. Put simply, people hope to win an argument by accusing their opponent of inflicting emotional violence upon them. Gaslighting is a real phenomenon that is no doubt also practiced by abusers on the Internet. The term should certainly be employed when appropriate, but the word carries too much freight for journalists to toss about lightly. ↩